The silhouette of Lancelot Nul

The project’s logistics….

Both the early Greeks and early Chinese told stories to explain philosophy, and with the rise of fiction in the 18th century, Western novelists and poets used literature to explore the nature of selfhood in particular. In modern times, a few authors ranging from Rebecca Newberger Goldstein (36 arguments for the existence of God) to Neal Stephenson (The baroque cycle) still use fiction to creatively explore religious and philosophical ideas, but Jostein Gaarder (Sophie’s world) set himself apart from the rest by explicitly creating a teaching novel about Western philosophy.

Complementing Sophie, Silhouette introduces readers to Chinese philosophy, homing in on the Confucian, Buddhist and Daoist notions of selfhood. To grossly generalize,

- in Confucianism, the self is a knot, the sum of ties to the people around it;

- in Buddhism, the self is a thought, a false perception from a habituated mind;

- and in Daoism, the self is a clot, the momentary coming together of aggregates entirely defined by just its own circumstances and not by anything beyond them.

All these sharply contrast with modern Western individualism that usually treats the self as a bordered, persisting and independent essence. Silhouette playfully explores such comparisons and contrasts.

As it happens, fiction is the best venue for fostering a dialogue among these isms, and when the dialoguers include university dons and street vendors, Amish youth and the urban houseless, crafty mayors and craftier monks as well as ghosts, golems and one dog … there are a lot of quirky selves to talk about the self. (One of the eighteen correspondents in this slightly out-of-sync world even happens to be a tree under which Lancy sits, framed by its own assumptions about time and space.)

Passionately invested in this project, I seek an agent and publisher who will stick with me for the long haul, people who will constantly question my claims, persistently push my prose, and anxiously edit out my alliterations, all the while still believing in the benefit of making Chinese thought accessible to the general reading public. I am proposing a trilogy (or one exceptionally long book) introducing Chinese philosophy through Lancy’s narrative, complete as follows:

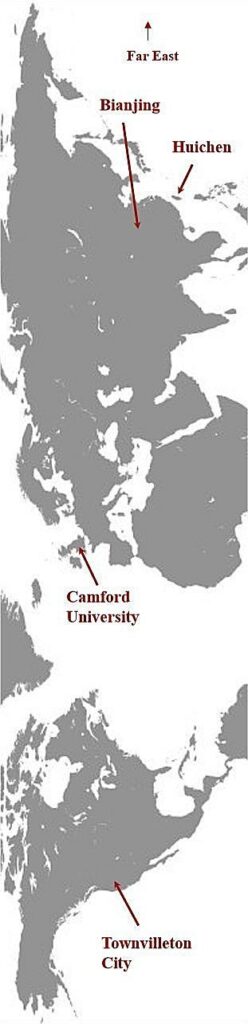

- Part one: Camford University (in which Confucianism preponderates) at 158,000 words;

- Part two: Huichen (Buddhism) at 203,000 words; and

- Part three: Townvilleton City (Daoism) at 215,000 words.

As a whole, Silhouette no doubt sets itself apart from other projects in terms of length, both because it aspires to be a reliably thorough introduction to Chinese thought and also because adding entertainment to education does make for a longer reading journey. Yet it’s the narrative that unifies and enlivens the learning, bouncing the reader along at a brisk pace on an excursion that – I hope – never seems long and always seems worth the investment. I can send the whole of Silhouette to my prospective agent, not only to let them judge that claim for themselves, but also to give them their own chance to think about (and to think with) Chinese philosophy. I’m a teacher before all else.

In sum, The silhouette of Lancelot Nul is an attempt to bridge Western and Chinese understandings of selfhood which, given the current uneasy state of relations, would alone justify the project. With the stakes getting higher and higher, we at least ought to learn about one another before we “other” one another. Even so, that’s not why I wrote it. Instead, it’s because I grew up “a kid from the prairie†– from Aurora, SD, population 500 – seeing my self and my world in a certain way, and thusly habituated, I didn’t even know enough to ask questions about what my self and my world were. I didn’t even realize there are other legitimate ways of perceiving self and world until I encountered another culture’s perception of them – in this case the perception of early and medieval China. I intend that, in Silhouette, we learn about another culture’s notion of selfhood and, at the same time, learn about our own through contrast. With their own self in tow, readers will be implicated in Lancy’s quirky story when they realize there are other ways of understanding it.