The silhouette of Lancelot Nul

A modern lighthearted story

unpacking

early Chinese philosophy

More than a billion people in the world today claim intellectual inheritance from Ancient Greece. More than two billion are the heirs of ancient Chinese traditions of thought.

– R.E. Nisbett, The geography of thought.

Almost thirty years ago, Sophie’s world famously introduced Western philosophy through an easy-to-access modern narrative, and after forty million copies in sixty languages, it continues its popularity, even now being repackaged as a series of graphic novels. Following its lead, The silhouette of Lancelot Nul explains the basics of Chinese thought by telling a relatable, lighthearted story as Lancy tries to justify his owning a little bit of space in the world and a brief moment of time in history.

Straddling the genres of nonfiction and fiction, Silhouette introduces Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism from first axioms to daily practice, and it specifically focuses upon their respective questions about selfhood:

- Is the self defined via universal patterns, like all things in the material world?

- Or is it a nexus of only its most immediate circumstances in both time and space?

- Or is it an independent, persisting thing, a soul unchanging within life and even across lives?

- Or is it a bundle of ties to others with no essence or individualism inside that knot?

- Or is it a depressing delusion nurtured through desire, desire that leads to attachment, and attachment that inevitably breaks because everything is impermanent?

And in all the above, is “the self†in fact “your selfâ€? These aren’t just the abstract questions of ancient China; they can be asked of us today, evoking our own lived experience. Winner of the highest national awards for both his teaching and his academic books about these questions, Silhouette’s author now explores them via a modern story, one that shadows a mother in search of her adult son.

With her Lancy missing for several years now, Laura Nul had reached out to his former teachers, employers and friends to peer into his state of mind and track his movements from Camford, England, then to Huichen, Taiwan, and finally to Townvilleton City in the Pacific Northwest. Their diverse and often quirky perspectives coalesce into this often-lighthearted, always-colorful tale of Lancy’s progress through a world that’s a bit out-of-sync with the one we know. He seemed to have started out well, that kid from the American prairie winning a prestigious scholarship to an even-more-prestigious British university, but maybe it was his peculiar choice of degree program there – a Bachelor of Pondering (BPo) in the discipline of Chinese thought – that derailed him. Maybe his linguistic inabilities finally got the better of him. Or maybe his subsequent career choices were questionable. (Exactly how did a Midwestern farm boy become a professional mourner at Chinese funerals? And then how did he manage to screw it up, like every other occupation he attempted?)

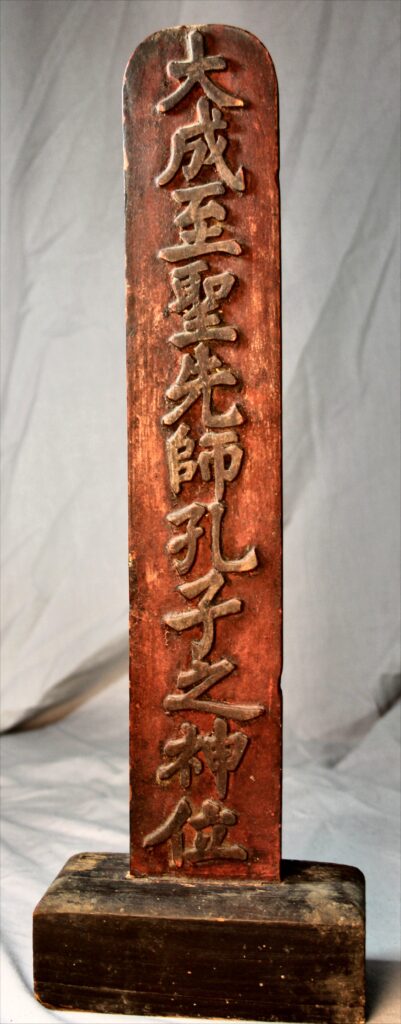

to Confucius

Resorting to an epistolary format, Silhouette consists of eighteen letters from people who either knew Lancy well or figured into major events of his life. Tutors and classmates at Camford University attest to his growing crisis in confidence as he struggled with both the Chinese language and the university’s traditionalism, resulting in Lancy almost failing his final examinations. In Taiwan, employers and friends describe his disastrous job experiences, ranging from teaching English at the unlicensed cram school “Its English time!†[sic], to starring as “the Enigma†on a glitzy television game show in which enthusiastic contestants feverishly competed to decipher Lancy’s Chinese. From the mayor to the houseless, the colorful characters of Townvilleton City later recount how Lancy showed up penniless and memoryless, begging for spare change on the Tumwata Bridge, but also how he gradually became more settled with himself by eventually getting rid of that “self.†Yet how far did he go to get rid of it?

of ÅšÄkyamuni Buddha

Both nonfiction and fiction, this upbeat novel intends to educate and entertain readers. “I now get the basics of Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism,†they’ll conclude. “And as for that stuff about building a golem in the dungeons beneath Camford University, about ‘seeing’ the world through the nose of that stray dog in Huichen, and about visiting the annual ‘Field of flames’ marketplace where religions sell their respective hells, out-scaring one another to attract frightened customers, in Townvilleton City … that was pretty cool, too.â€

Throughout, Lancy’s unusual and often humorous tale is interwoven with two other narratives that address each chapter’s themes of self-construction. Linden Angerbell’s storyline from twenty years earlier consists of cassette transcripts from eighteen tutorials during her last year at Camford as she readied herself for her own final examinations in Chinese thought. Her aging tutor, Dalton Fu, had the highest hopes for brilliant Linden and was even grooming her to someday replace him and preserve the disappearing discipline of autology. In his rooms at St. Polycarp’s Hall, they debated one’s own awareness of body and self while Linden happened to be nursing a hangover; while listening to Fantasia and watching the quad below, they discussed how religion is a mood-setting musical score in life’s background. During their many field trips, they witnessed the construction of a Buddhist golem, and they got expelled from St. Polly’s chapel after spending the whole of an evensong service arguing about how the self gets habituated. Outside the tutorials, Linden babysat Dr. Fu’s rambunctious grandson J.Artus, and she helped her tutor bury his dead cat Peeve in Tawny Meadow. Yet throughout the year, Linden’s academic interest in studying Chinese thought waned because her experiential interest in the same waxed.

The final narrative reaches into the distant past. Emperor Huizong in 1115 CE refocused the civil service examination from Confucianism to Daoism (a true event) and so Wu Youren (a fictitious figure) compiled his Dao in a fly’s head, a cheat book in a Q&A format for examinees to smuggle into the next triennial test. He composed this book at the western window of a four-story tower – tall for the time – overlooking the imperial garden in Bianjing, the capital of China and biggest city in the world during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). A devout Buddhist in an era when the weakening court hated Buddhism, Wu Youren used sutras to navigate the friction between Confucianism and Daoism, trying not to leave any Buddhist fingerprints behind as he explored all three. Throughout the year that he gave himself to assemble his handbook, he harbored suspicions about his landlady and occasional discussion partner, “Demon Mama,†who regularly occupied the eastern window of the same tower room. She was equally suspicious of him.

from Five Thunders Daoism

Silhouette’s three storylines not only support one another when addressing Chinese philosophy generally and the nature of self specifically, they also become a single interwoven narrative. Linden was destined to translate The Dao in a fly’s head into English, and Lancy later pursued Linden in Taiwan to get that translation.

Where does it all begin? The first of the eighteen chapters, “Mid-slide,†is available as a pdf at the bottom of this page. Please enjoy your self.